The Asphalt Jungle is a celebrated film noir movie by John Huston, the celebrated director of celebrated film noir movies. He gave us films like The Maltese Falcon, The Treasure of the Sierra Madres, and Key Largo. His body of noir work is impressive, but I think this might be his best. I also think this might be the best noir film I’ve ever seen (and I’ve seen quite a few).

Basically, The Asphalt Jungle is a heist movie revolving around a plot to steal $500,000 in diamonds. The people doing the plotting are a shady group of characters. As Huston said in his introduction to the film, “You might not like them but you will find them fascinating.”

There’s Doc (Sam Jaffe), the criminal mastermind. He planned the heist in prison and begins initiating it the moment he’s released. He wants the money so he can flee to sunny Mexico and romance young girls.

There’s Emmerich (Louis Calhern), the financier. A crooked lawyer, he puts up the money for the heist. With the score, he hopes to continue supporting his life of luxury and decadence, symbolized by his mistress (Marilyn Monroe).

There’s Gus (James Whitmore), the driver. His job is to make sure everyone disappears into the night without a trace, a task that proves easier said than done.

There’s Ciavelli (Anthony Caruso), the safe cracker. His job is to beat the state-of-the-art technology that stands between the gang and the money.

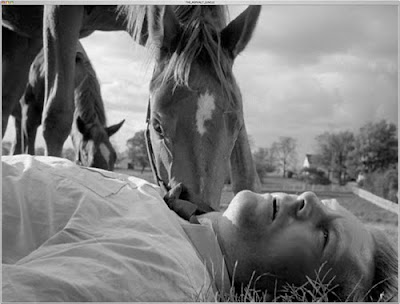

There’s Dix (Sterling Hayden), the muscle. He’s a small-time thug who addicted to horse races, probably because they remind him of the Kentucky farm his family lost in the Depression, something he desperately wants to buy back someday.

Now, crime movies often have stereotypical characters, but thankfully the main cast never allows itself to fall into this trap. The actors present their characters as legitimate characters, human beings with fascinating personalities and intriguing motives. As an added bonus, the movie boasts a rather large collection of supporting actors (Jean Hagen, Barry Kelley, Marc Lawrence, Dorothy Tree, John McIntire) who are all fabulous. These minor characters help develop our understanding of the main characters, giving them depth and substance. For example, there’s Emmerich’s invalid wife (Dorothy Tree). This movie could allow us to simply see Emmerich as a sleazy lawyer who cheats on an invalid life with no screen time. But instead, this movie takes the time to show him visiting her on bedside, listening to her pleas and complaints about the way their relationship use to be. We see that he is wrestling not only with greed but guilt. When he commits suicide later in the movie avoid arrest, the gang mocks him. He would have only gotten a two-year sentence, they say. But because of this scene, we know Emmerich was trying to flee something worse than arrest.

Because no character in this movie is flat or one-dimensional, we see them as real people with real motives. This not only creates depth but suspense. Since this is a film noir movie made in 1950, we know how it will end. We know things will go badly for the gang. But the question is how will their foolproof plan fall apart? In every interaction between the characters, big or small, we see the chance for disaster growing. Because the characters are represented as real people with real motives, we see that anyone in this movie could be the undoing of someone else. We know everything will break and fall apart; what we don’t know is who will break it and why. That’s what we’re watching to find out.

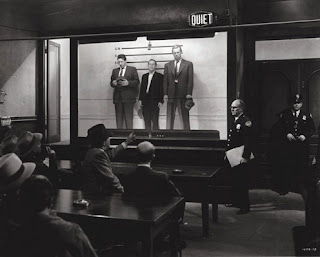

However, great performances and a great script aren’t the only attributes of this movie. Visually, it’s one of the finest film noir movies I’ve ever seen. The opening sequence – a sterile, empty, people-less city that seems to exist for one lone man, a cruising patrol car, and a moody soundtrack – tells you everything you need to know about film noir.

While watching The Asphalt Jungle, I recalled a recent conversation I had with some fellow movie buffs about the merits of the Motion Picture Production Code, also known as the Hays Code. The Code was enacted in 1930 by Hollywood to self-censor movies, making them acceptable for the general public. Today, the Code seems archaic (it also seems delightfully quaint or bitterly repressive, depending on your point of view). However, I’m not sure we would have a movie like The Asphalt Jungle were it not for the influence of the Hays Code. In fact, I’m not sure you would have the entire film noir genre.

Due to the Hays Code, the film industry wasn’t allowed to represent criminals or crime in a positive light. “The sympathy of the audience should never be thrown to the side of crime, wrongdoing, evil, or sin,” the Code warned. As a result, gangsters had to die in gunfights (Public Enemy), femme fatales had to meet fatal ends (Double Indemnity), and murderers had to walk death row, typically supported by a priest in their last earthly minutes (The Postman Always Rings Twice).

Now, most filmmakers resisted the Code in one way or another. Some found ways to get along with. Some found ways to cleverly subvert it. However, others found, under its restrictions, the chance to create profound metaphors for the human condition. Film noir is the prime example of this. Noir stories are always stories about people living on the margins of society. Most of them are criminals. Because of the Hays Code, these stories have a default ending: the protagonists go to jail or die (or sometimes both).

Filmmakers could only create one ending for these stories, so they decided to create one that reflects problems in art and life reaching back to the days of Sophocles and Euripides. In the hands of skillful directors like John Huston and Bill Wilder, the ill-fated film noir protagonist becomes a player in an existential drama, fighting against cosmic injustice. Film noir protagonists are lost, cynical, struggling, striving, deceitful, hurting, hurtful, and above all, lonely. They are lonely because they live, and ultimately, die alone. They’re trapped in their situation, with no one except themselves to rely on. All their hope and hard work is destroyed, inevitably, by either cosmic ironies or human frailty. Visually, the essence of film noir may be its dark shadows and lonely city streets. Philosophically, however, the essence of film noir is Jakes Gittes' (Jack Nicholson)’s look of complete anger and inability at the end of Chinatown as he realizes there is nothing he can do to make this situation right.

“It’s Chinatown, Jake.”

Film noir movies are always fatalistic, but I don’t think the genre itself is fatalistic. People love film noir movies. Somehow, they’re cathartic. Nobody really knows why. Nietzsche said people love tragic art because it allows them to confront the nihilistic Void of existence. Freud said people love tragic art because it’s a talking cure, something that can help them work out their psychological problems. That’s what they said; but they said a lot of things.

I love film noir. I don’t know why I love it, but I do. It's a genre full of bad endings and beautiful finishes.

As someone obsessed with noir, you've made me want to go back and watch this one again. I don't think I appreciated it quite so much the first time around. I mainly remember Marilyn Monroe's 5 seconds onscreen, which is probably why I rented it at the time.

ReplyDeleteIncidentally, have you seen In A Lonely Place? Not quite noir in the purest sense, but marvelous movie.